On the night of January 19, 2026, skywatchers across much of North America and Europe were treated to a rare sight: the aurora borealis, or northern lights, visible far outside their usual Arctic range. In some U.S. states well into the mid-latitudes, including parts of the Midwest and even southern regions, observers spotted shimmering green and red lights dancing across the sky. Understanding why this happened requires a look at how space weather and Earth’s magnetic field interact. (The Washington Newsday)

A Powerful Solar Eruption and the Resulting Storm

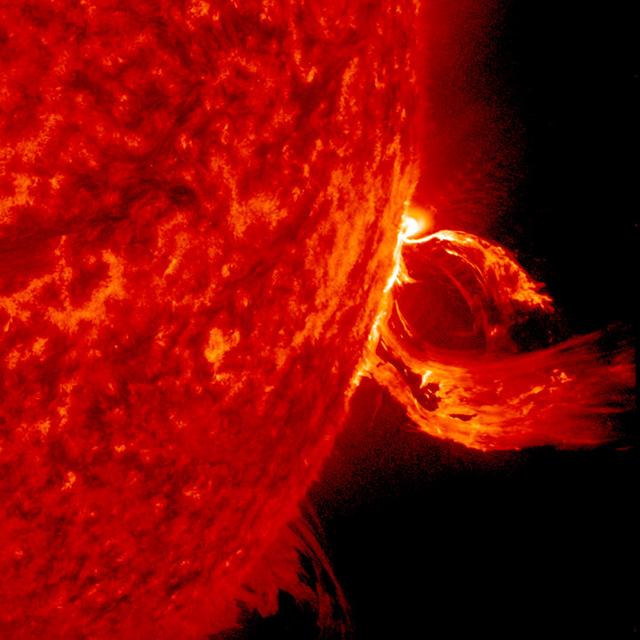

The event began on January 18, 2026, when the sun erupted with a powerful X-class solar flare. These flares represent the most intense category of solar eruptions and are often associated with large amounts of energy and charged particles being hurled into space. This particular flare launched a coronal mass ejection (CME) directly toward Earth. A CME is a huge cloud of solar plasma and magnetic field that, when it reaches our planet, can stir up major disturbances in Earth’s magnetic field known as geomagnetic storms. (The Washington Newsday)

By late afternoon on January 19, the CME collided with Earth’s magnetic field, triggering one of the strongest geomagnetic storms in years. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) reported that the storm reached G4 severe levels, a rating near the top of the geomagnetic storm scale and uncommon at this stage of the solar cycle. These high levels of activity marked a significant space weather event. (The Watchers)

Why Auroras Appeared So Far South

Under normal conditions, the aurora borealis is largely restricted to high latitudes near the Arctic Circle, where Earth’s magnetic field lines converge. Charged particles from the solar wind are funneled along these magnetic lines toward the poles, where they collide with molecules in the upper atmosphere. These collisions excite atoms and cause them to emit light, creating the auroral glow. (SpaceDaily)

However, during severe geomagnetic storms, the stronger disturbance pushes the region where charged particles interact with the atmosphere much farther from the poles than usual. In this case, the storm’s intensity expanded the auroral “oval,” making the lights visible across much of the northern United States, and in some cases as far south as parts of Alabama, Mississippi, and northern Florida. That level of southward visibility for the aurora is rare and typically signals a strong storm. (Queen City Newsfeed)

Several factors made this storm especially favorable for broad visibility:

- The strength of the CME and associated geomagnetic disturbance, which reached severe G4 levels. (The Watchers)

- A new moon phase around January 18, which reduced background sky brightness and made the auroras easier to see. (Forbes)

Impacts Beyond the Sky Show

While the aurora was a beautiful spectacle, geomagnetic storms of this size can also have practical impacts. Strong storms can disrupt satellite operations, interfere with GPS navigation and radio communications, and induce electrical currents in power grids that engineers must manage. These effects do not pose a direct health risk to people on the ground, but they can affect technology that modern society depends on. (Queen City Newsfeed)

When We See Events Like This

Solar activity, including flares and CMEs, follows an approximately 11-year solar cycle. We are currently near the peak of this cycle, meaning intense space weather events are more likely than during the solar minimum that follows the cycle trough. However, storms severe enough to make auroras visible far from the poles remain relatively uncommon, which is why the January 19 event drew so much attention. (phys.org)

Earth’s Greatest Light Show to the Classroom

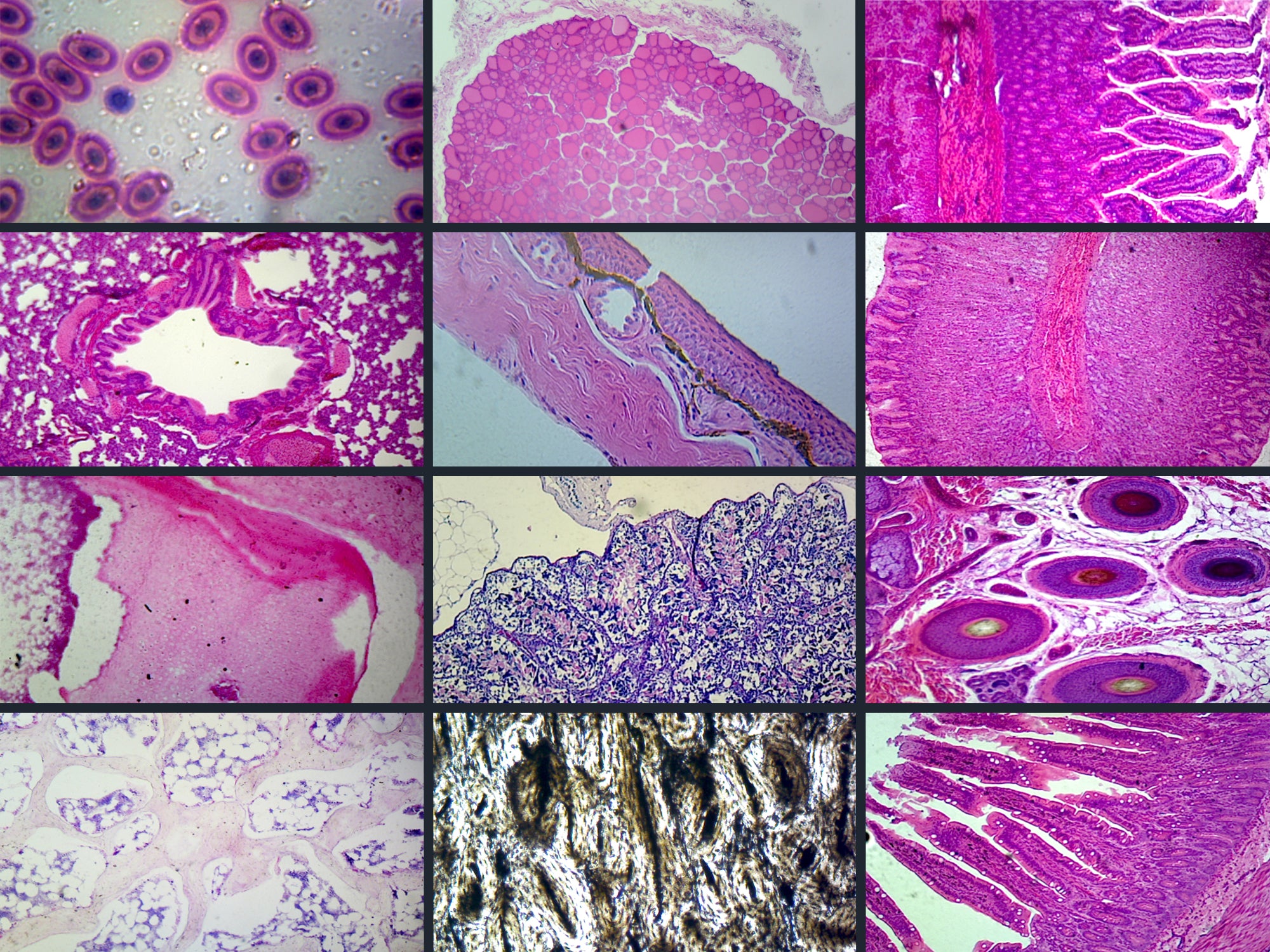

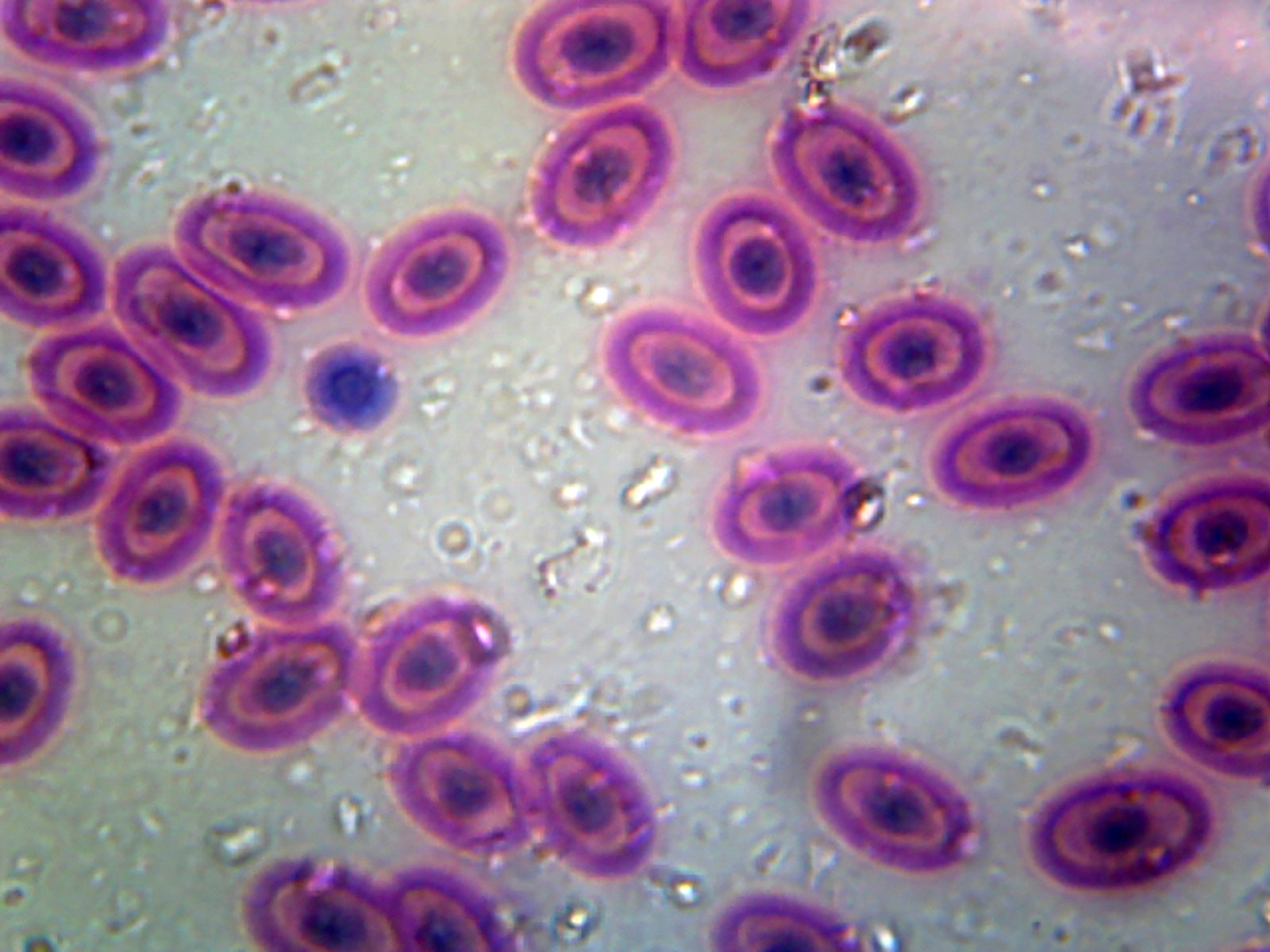

The aurora borealis is often described as one of nature’s most breathtaking light shows. Charged particles from the sun collide with gases in Earth’s atmosphere, releasing energy in the form of light. Different gases and energy levels produce different colors, creating the glowing greens, reds, and purples seen during strong solar storms.

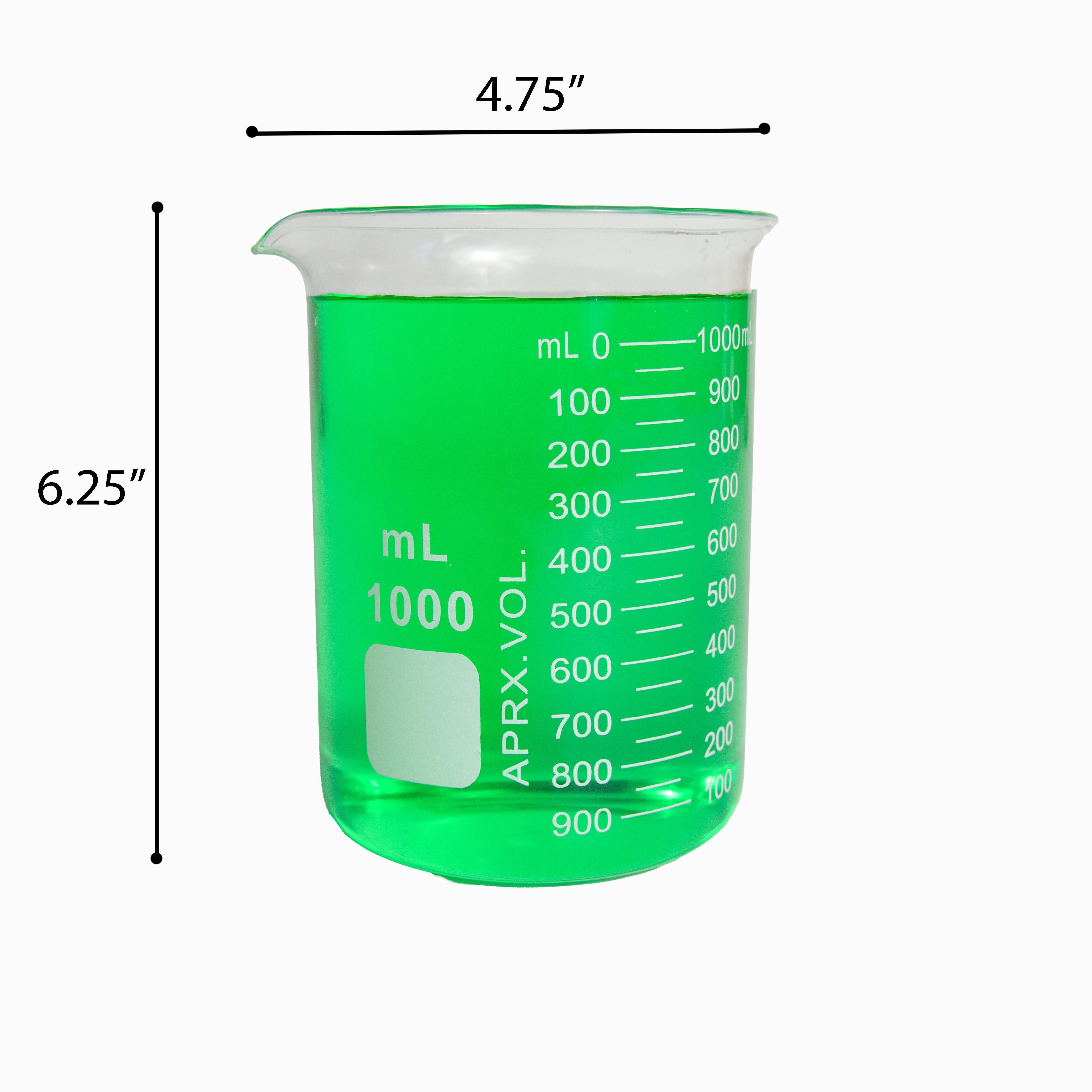

This same idea, energy being absorbed and re-emitted as visible light, is a powerful concept for students to explore hands-on in the classroom.

Many classroom light demonstrations mirror the physics behind auroras on a smaller, more controlled scale:

- Spectrum tubes and power supplies help students see how different gases emit distinct colors when energized, similar to how oxygen and nitrogen glow in the upper atmosphere during an aurora.

- Light boxes, prisms, and diffraction gratings allow students to explore how light separates into wavelengths, reinforcing why auroras display multiple colors.

-

Sound and wave demonstration tools connect naturally to space weather discussions by showing how energy travels through waves, whether as light, sound, or electromagnetic radiation.

Using these tools, students can move from observing a spectacular real-world phenomenon to understanding the physics that makes it possible.