In the chemistry or biology classroom, beakers are essential workhorses. They hold solutions, facilitate mixing, and support countless experiments throughout the school year. While glass beakers have been the traditional standard, polypropylene beakers offer compelling advantages that make them increasingly popular in educational settings. Here's why polypropylene deserves serious consideration for your classroom lab.

Safety First: Shatter-Resistant Construction

The most significant advantage of polypropylene beakers is safety. Glass beakers, when dropped or knocked over, can shatter into sharp fragments that pose injury risks and create cleanup challenges. Polypropylene beakers are virtually unbreakable under normal classroom conditions. When students accidentally drop them (and they will), the beakers bounce rather than break.

This shatter-resistant property is especially valuable in middle and high school labs where students are still developing laboratory skills and spatial awareness. It reduces the risk of cuts, eliminates the hazard of glass shards mixing with chemical spills, and minimizes the anxiety that comes with handling fragile equipment.

Chemical Resistance and Versatility

Polypropylene exhibits excellent chemical resistance across a wide range of substances commonly used in educational labs. It's compatible with most acids, bases, and aqueous solutions at room temperature, making it suitable for the majority of classroom experiments.

Polypropylene resists:

- Dilute acids (hydrochloric, sulfuric, acetic)

- Bases and alkaline solutions

- Aqueous salt solutions

- Alcohols (though prolonged exposure to some organic solvents should be avoided)

This broad compatibility means you can use the same set of beakers for biology, chemistry, and earth science applications without worrying about degradation or contamination.

Lightweight and Easy to Handle

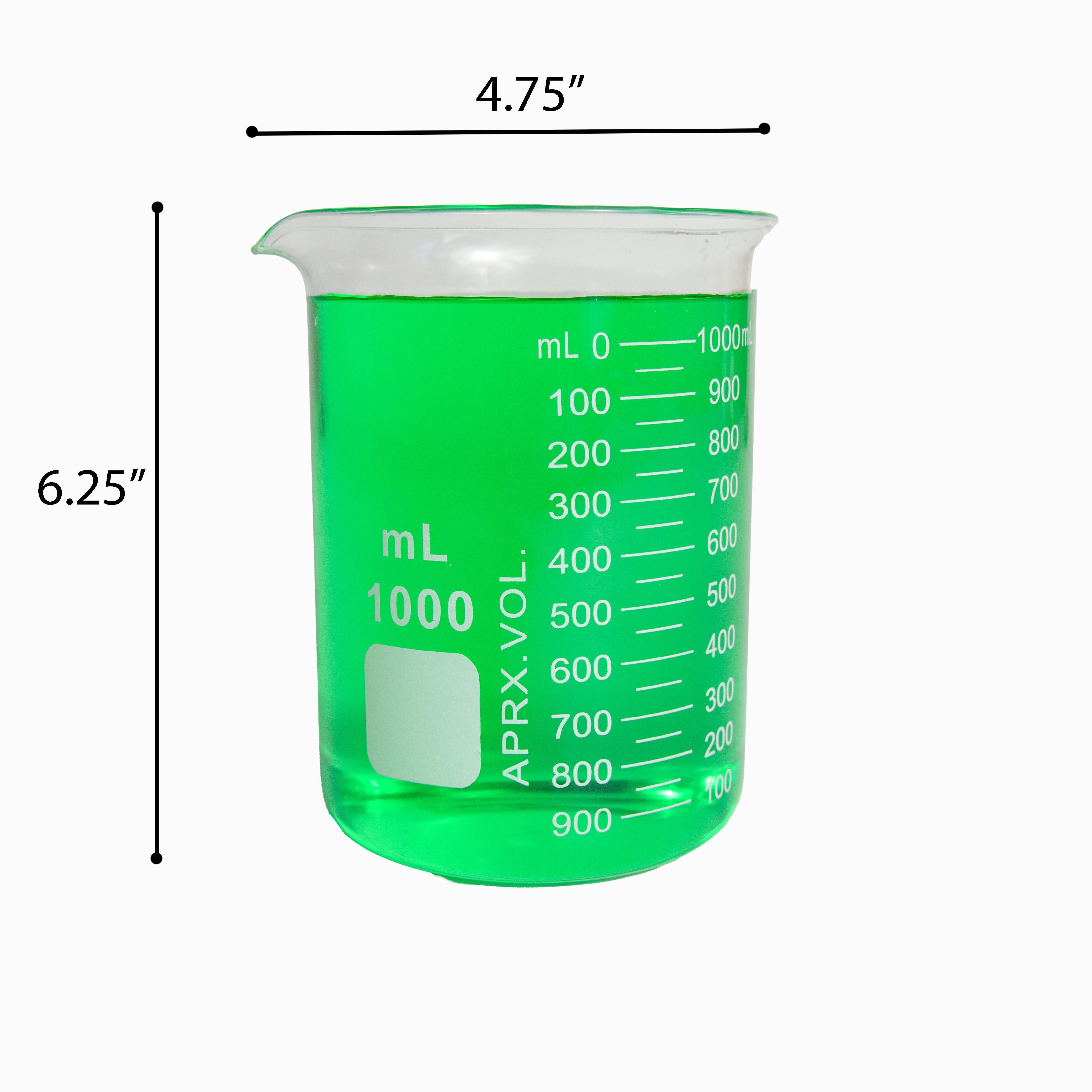

Polypropylene beakers weigh significantly less than their glass counterparts. A 1000mL polypropylene beaker weighs a fraction of what a glass beaker of the same capacity weighs. This makes them easier for students to handle, pour from, and transport between lab stations.

The reduced weight also matters for storage and classroom setup. Teachers can more easily carry multiple beakers at once, and students can manage larger volumes without strain. This is particularly helpful when working with younger students or when setting up demonstrations that require moving equipment around the classroom.

Cost-Effectiveness and Longevity

While individual polypropylene beakers typically have a similar initial cost to glass, their durability translates to significant long-term savings. Glass beakers break regularly in active classrooms, requiring constant replacement. Polypropylene beakers can last for years, even with heavy student use.

The reduced breakage also means less downtime. You won't need to halt a lab activity because half your beakers are broken, and you won't spend budget dollars replacing equipment that should have lasted much longer. Speaking of dollars, now's the time to stock up as many of our polypropylene beakers are on sale.

Transparency and Graduations

Modern polypropylene beakers offer good transparency, allowing students to observe reactions, color changes, and solution levels. While not quite as crystal-clear as glass, the visibility is more than adequate for educational purposes.

Molded or printed graduations provide volume measurements. Though polypropylene beakers aren't precision volumetric instruments, they're perfectly suitable for the approximate measurements required in most classroom experiments. For teaching purposes, they help students understand the difference between beakers (approximate volume) and volumetric flasks or graduated cylinders (precise volume).

Temperature Considerations

Polypropylene has an important limitation: it has a lower heat tolerance than borosilicate glass. Polypropylene typically withstands temperatures up to about 135°C (275°F), while borosilicate glass can handle much higher temperatures.

For classroom use, this limitation is often manageable. Many educational experiments occur at room temperature or involve gentle heating. Polypropylene beakers work well for mixing solutions, growing cultures, holding specimens, and conducting reactions that don't require high heat. For experiments requiring boiling or high-temperature heating, glass beakers or other heat-resistant vessels remain necessary.

This creates an opportunity to teach students about material properties and selecting appropriate equipment based on experimental requirements.

Autoclavable for Biology Labs

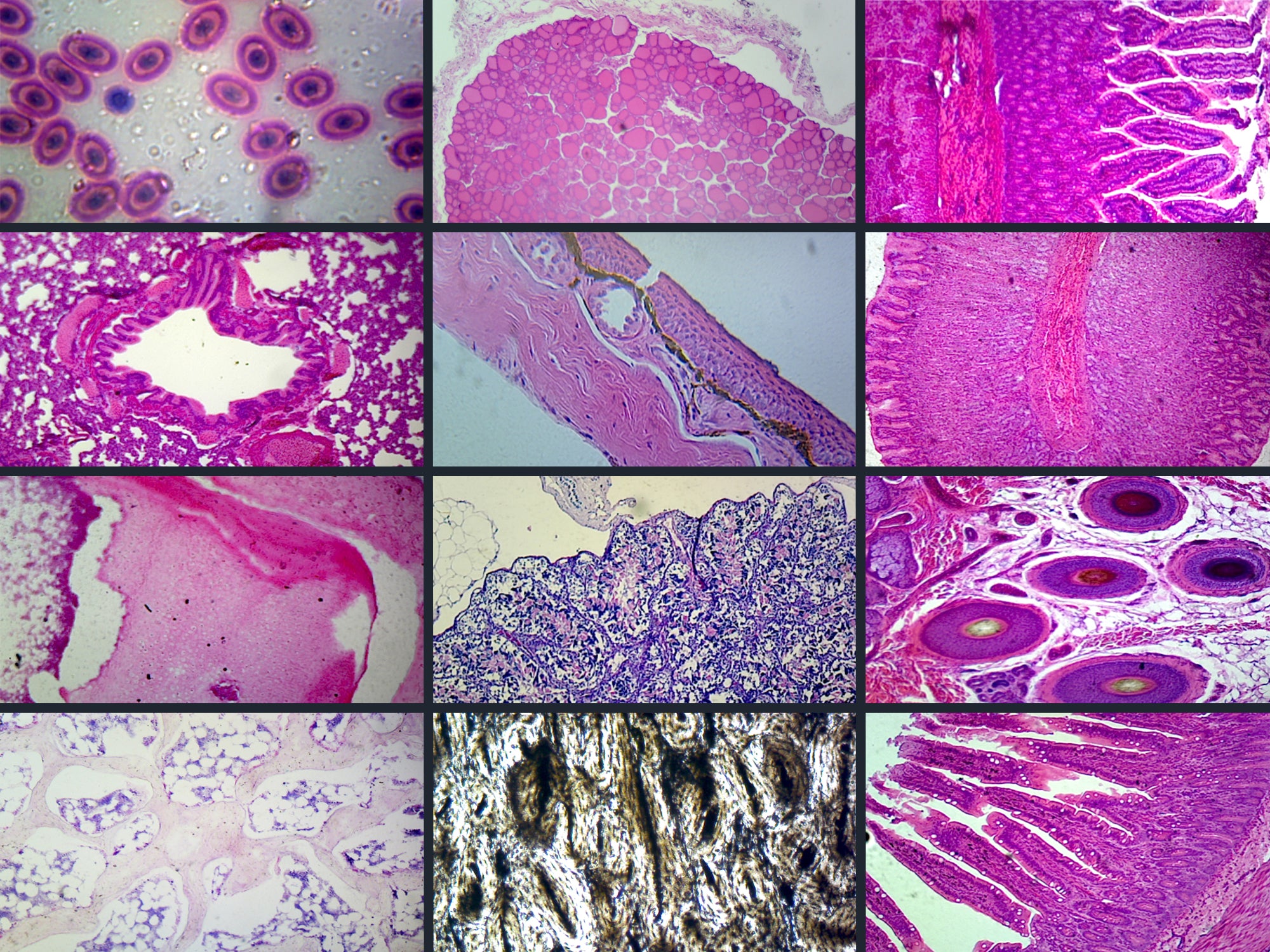

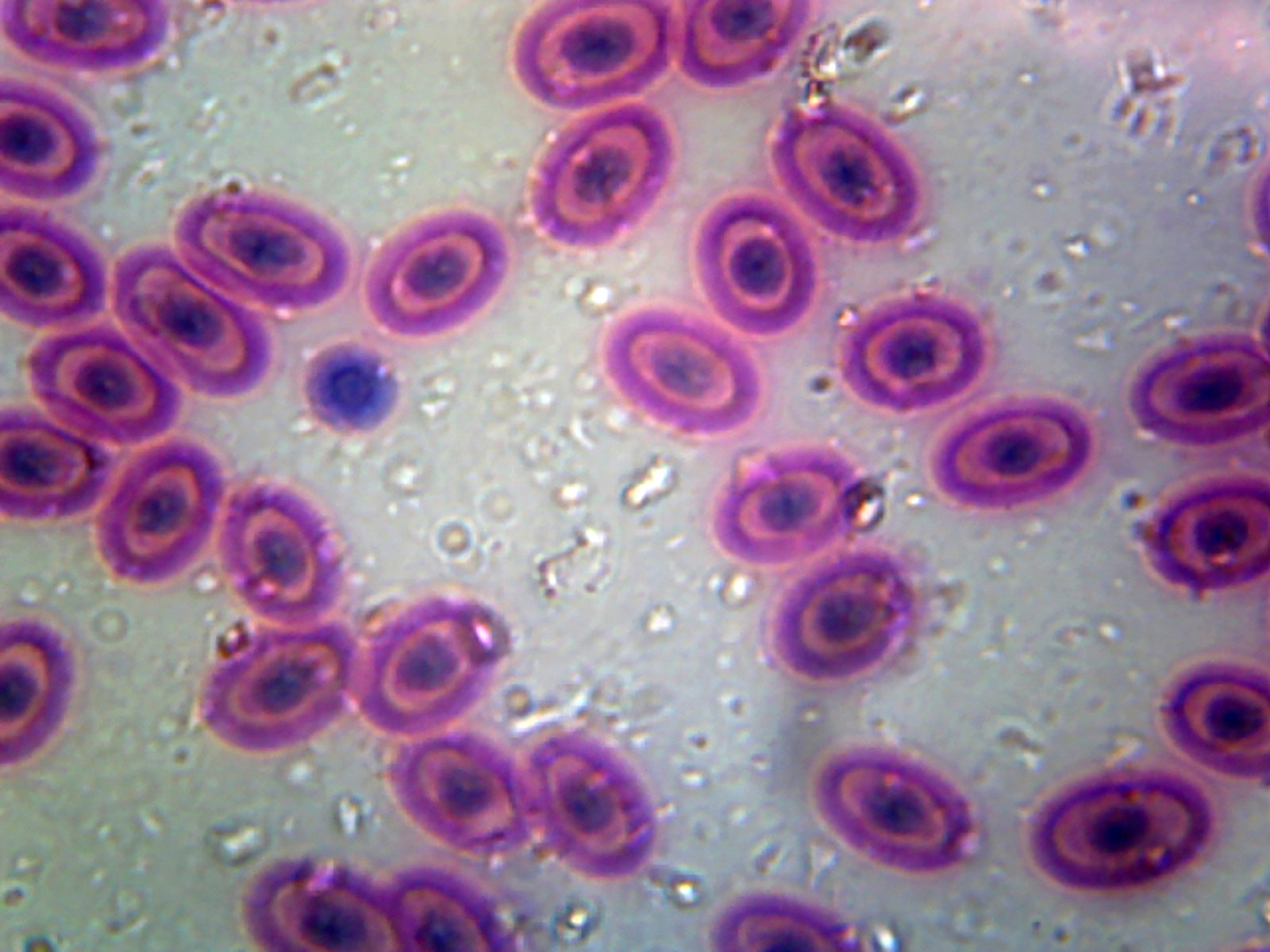

Many polypropylene beakers can be autoclaved at 121°C, making them suitable for sterilization in biology and microbiology applications. This is a significant advantage for life science classrooms where sterile technique matters.

The ability to autoclave polypropylene beakers means you can prepare sterile media, culture vessels, and solution containers without investing in separate autoclavable glassware.

Environmental Considerations

Polypropylene is recyclable (resin code #5), and its longevity means fewer beakers end up in landfills compared to frequently broken glass. While glass is also recyclable, the practical reality is that broken lab glass often can't go into standard recycling streams due to contamination concerns and safety issues.

The reduced shipping weight of polypropylene also means lower transportation emissions when ordering supplies.

Making the Right Choice

Polypropylene beakers aren't a complete replacement for glass in every situation, but they're an excellent primary choice for general classroom use. Consider maintaining a mixed inventory: polypropylene for everyday student use and routine experiments, with a smaller set of borosilicate glass beakers reserved for high-temperature work.

This approach maximizes safety, minimizes replacement costs, and ensures you have the right tool for every experimental need. Your students get hands-on experience with durable equipment, and you get peace of mind knowing that a dropped beaker won't derail the day's lesson.